Having covered momentum in the last series, I now look to value. It is a subject that becomes increasingly important with experience because it is the only strategy that lasts the test of time. I will outline value through the lens of the Coca-Cola (KO) share price since the 1960s.

Value investing seeks out situations that are trading below their intrinsic value. For the corporate raider, that could be valuable assets such as property, securities, plant and machinery, or even intellectual property. More often, it is an upbeat view of the company’s growth prospects, using reasonable assumptions. Value might also be found in a bond with a more attractive yield or a commodity trading below a level it might reasonably be expected to. Provided the value investor does the research and has the skills and patience, they routinely make money, albeit with the occasional hiccup.

Value is a robust investment strategy. It may not get all the glory, like high growth stocks, but if well-implemented, it is a reliable source of market-beating returns that can be generated in a wide range of market conditions. Buying something that is undervalued is a basic and sound investment principle, one that should never be ignored. By the same line of reasoning, any investment that is not expected to deliver value should be avoided.

Buffett once said that investors who distinguish between growth and value are confused.

“Investment managers who glibly refer to Growth and Value styles as contrasting approaches to investment are displaying their ignorance, not their sophistication. Growth is simply a component - usually a plus, sometimes a minus - in the value equation.”

He meant that you could compare fast and slow-growing companies, but the valuation method for both companies should be the same. The growing company could be underpriced, and the slow-growth company overpriced, or it could be the other way around. A company’s intrinsic value is determined by the present value of its future cashflows or its breakup value. If the market price is below intrinsic value, you should buy. If it isn’t, find something else that is.

Yet it is common parlance in markets to use the terms growth and value, referring to fast and slow-growth companies, which is entirely reasonable. I also use the term Value to describe asset-heavy companies in the Money Map, but I probably shouldn’t (I may switch to cyclicals). Most investors count companies with sales and earnings growing above (say) 10% per annum as growth stocks, with everything else being dismissed as value. As I said, parlance rather than science, but we know what it means.

Skilled value investors are more precise, and when they identify value, they see a situation offered at a price below its intrinsic value, with a margin of safety to boot. The idea is the market will eventually see what they see and revalue accordingly.

Some situations can take a long time to reward investors, especially when a company or an industry is undergoing a major change. Sometimes, it can be quick, such as the bid for Keywords Studios, which came six days after my note in ByteTree Venture, returning 73%. There are also value traps, which are companies that are dying slowly, which might not be obvious at the time. A good example would be Blockbuster Video in its latter years, which was cash-generative but never cheap for the simple reason that its intrinsic value was heading for zero.

KO is a well-known company with a rich history. Unlike many companies from the 19th century, today, it still does roughly what it did back then, so it is useful as a case study for long-term valuation.

The Valuation of Coca-Cola (KO)

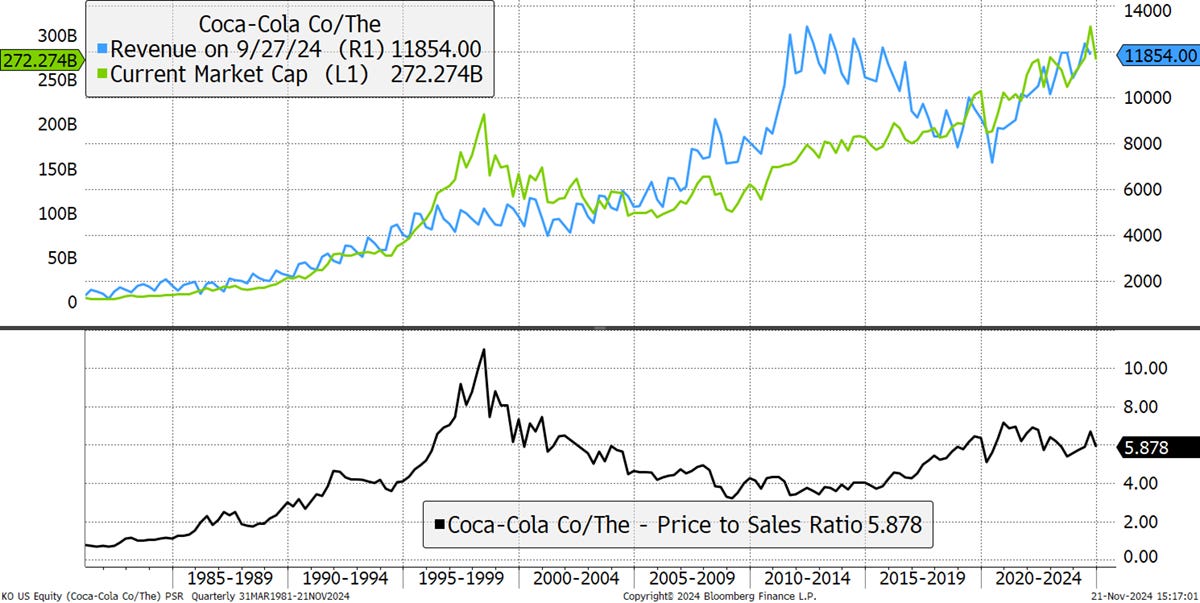

I will start with the price-to-sales ratio using 44 years of data available on Bloomberg. This is a simple measure comparing a company’s sales to its market capitalisation (total shares times share price). A company has many different variables, but price and sales are important ones and hard to manipulate.

In 1980, an era when equities were dirt cheap following a decade of inflation, KO had quarterly revenue of $1.3 bn (annual $5.6 bn) and a market cap of $4.1 bn. As a result, the price-to-sales ratio (PSR) was 0.7x. By June 1998, the market cap had grown to $211 bn and annual sales to $18.7 bn with a PSR of 11x. After the 1998 high, it took 16 years for the share price to make the next new high, and KO shares briefly managed to trade below 1998 levels during the pandemic, which came 22 years later.

Coca-Cola Price-to-Sales Ratio

That’s a long time for a large-cap growth stock to stall, but not only that, in 2014, sales had picked up on the back of acquisitions, and the shares traded on 4x sales for several years. Since 2015, they have risen back towards 6x sales.

I can illustrate the outsized gains of the stock, compared to the growth of the company, by rebasing the market cap and the sales to 100 in 1981. Between the start and the 1998 peak, sales had risen 4x, earnings 10x, while the share price had risen 46x. This is why investors get excited by growth. It’s not the sales or the profits that end up making the most money, but the increase in the multiple that investors are prepared to pay for growth. The multiple expansion was 11x more than sales and 4.5x more than profits over the 17-year period. The chart also shows the price-to-earnings ratio below.

Coca-Cola Price-to-Sales Ratio with Profits

There are other important points behind the change in the share price. In the 1990s, sales grew quickly as globalisation bore fruit. Profit margins surged with economies of scale. After the credit crisis in 2008, KO took advantage of cheap borrowing, geared up the balance sheet and resumed buybacks. By 2024, 28% of the equity has been repurchased by the company for cancellation. Fewer shares for the same company boosts the share price, even if it’s not money well spent. Then there was the transition from bottler to marketeer, where production was outsourced, resulting in the number of employees today being around half the level in 2013. Much has changed, but the products stay the same.

Buffett and Munger bought KO in 1988 after the stockmarket crash of 1987. Good call, as the PSR was 2x, and the growth rate picked up to 10%. Yet, by 1998, the PSR was 11x and the PE 55x, while growth had been sliding. In 1996, sales grew by just 3.6%, in 1997 by 1% and marginally contracted in 1998. Yet the shares carried on surging until the music finally stopped.

The real mystery is why investors chased the growth story in 1998 after growth had stalled. Investors were slavishly purchasing KO into the price surge with the full knowledge that the company was no longer growing. It’s a strange old thing that also works in reverse. Why were investors so adverse to KO in 1980 when the shares were undervalued, yet oblivious to the excessive valuation in 1998? It is a great mystery why the market can ignore facts staring at it in the face, and it’s not just KO. Booms and busts have been with us since the beginning of time.

For the KO date pre-1980, hat tip to @vitaliyk and the Coca-Cola website.

KO revenue

1965: $500 m

1972: $1.9 bn (up 3.7x since 1965)

1985: $7.9 bn (up 4.2x since 1972)

Despite the rise in sales between 1972 and 1985, the KO share price fell by 75% in the 1974 crash. It had been one of the nifty fifty stocks that dominated the momentum trade at the time. After the peak, it took KO 13 years to recover despite growing sales throughout the period.

Coca-Cola Share Price 1960 to 1985

Even without perfect charts and data, we can deduce that KO was trading at 5x sales in 1965 while growing sales at 21% p.a. By 1972, KO remained at 5x sales as the share price had matched the company’s growth. The shares collapsed in the crash of 1974, and by 1980, the shares were dirt cheap on 0.7x sales. That was the bargain of a lifetime.

Coca-Cola has a rich history, dating back to 1886. It is one of the greatest brands ever created, and its core business, selling refreshing sweet drinks, has remained constant. The long-term share price tells you as much about Coca-Cola as it does the state of the world. In the 1960s, stocks soared as the post-war economy boomed. In the 1970s, they crashed under the weight of inflation. They soared again in the 1980s and 1990s only to crumble in the noughties. In the teenies, they recovered, and today, they trade on a PSR of 5.9x, which is historically high and slightly higher than in 1972 before the crash. Yet back then, it was a growth stock, whereas today, it is pedestrian. Growth is forecasted to be 0.9% this year and 3.9% next.

Since 1965, Coca-Cola has broadly been the same business it always has been. KO shares are a little scarcer due to buybacks, and the company’s presence and number of brands have grown. But it’s still a beverage company. In that sense, a KO share is a constant, yet the stockmarket sometimes offers it at 0.7x sales and, at other times, 11x. The 60-year average is 4.2x. For such a steady and high-quality business, the swings have been remarkable.

The stockmarket rewards some companies and punishes others, but the right price is always found in the end. In the next parts of this series, I shall examine other valuation measures, such as enterprise value, cash flow, book value, what happens when growth slows, trading cyclical stocks, and more. When I have run out of interesting things to say, I will explain how I screen 3,000 stocks daily in search of value at ByteTree. On 5.9x sales, don’t expect KO anytime soon.

A Week at ByteTree

In recent issues, The Multi-Asset Investor covered Trump’s Impact on Financial Markets and, this week, Gilts in a Low-Growth Environment.

There was also the Venture monthly portfolio review, which is jam-packed with value stocks from around the world.

In Atlas Pulse, Opposites Attract – Gold Can No Longer Ignore Bitcoin, I looked at how Gold and Bitcoin have become an inseparable pair.

Finally, in ByteFolio, Bitcoin has been on a winning streak this week, with the price reaching a new all-time high of $99,500 early Friday morning. What is clear is that the US is driving this rally with friendly government policy. How long will the rest of the world remain on the sidelines?

Have a great weekend,

Charlie Morris

Founder, ByteTree.com

We would love to hear your feedback, so please share your thoughts in the comments. It would really help us if you could like, restack/share this update and subscribe to our Substack. Thank you so much for your support!