“A government bond is a debt security issued by a government to support spending and obligations. Government bonds pay bondholders periodic interest payments called coupon payments. Government bonds issued and backed by national governments are often considered low-risk investments. Government bonds issued by a federal government are also known as sovereign debt.”

Source: Investopedia

Governments used to borrow money to finance wars and pay back their debts after declaring victory. These days, there are governments that borrow money to cover the day-to-day expenses of running the country and governments that live within their means. In this short piece, I shall attempt to describe the impact of these choices through the lens of the UK and Switzerland.

Last year, the UK government raised £1.1 trillion from taxes but spent £1.22 trillion. The taxes mainly come from income tax, national insurance, VAT, and corporation tax. Most of the spending goes to health, pensions, social security, education, and defence.

The difference between what the government receives and what it spends is the surplus or the deficit. In 2024, the UK spent more than it received, and so there was a £122 billion deficit. In Switzerland, the government spent less than it received and had a modest budget surplus.

Budget Surplus/Deficit

In 1997, the UK government, under John Major, managed to deliver a surplus. Tony Blair then took office, and by 2001, the UK budget had returned to deficit where it has remained ever since. The deficit ballooned in 2008, after the financial crisis, only to blow out again during the pandemic. Despite all of those years labelled “austerity” while George Osborne was the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the UK Treasury never even got close to a balanced budget. The result of successive deficits saw the level of borrowing increase.

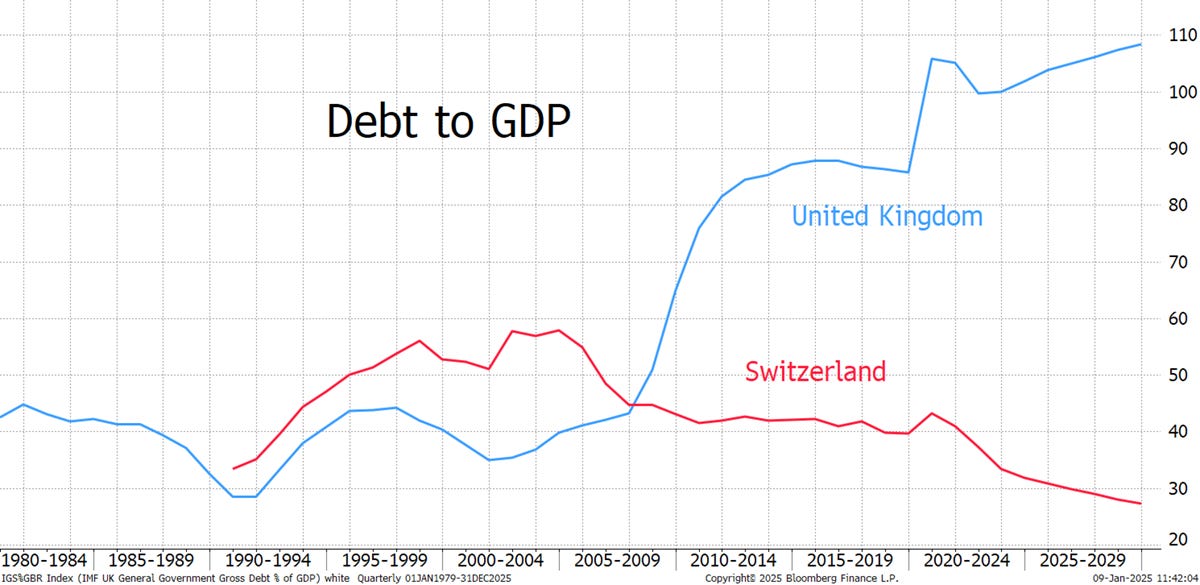

If a government has deficits year after year, they soon add up. The UK now has a national debt of £2.8 trillion, which is often shown as a percentage of the economy. The UK GDP was roughly £2.54 trillion last year, so the debt has grown to a size that is slightly larger than the economy.

Some believe that growing the nation’s debt was unavoidable, but by consistently balancing the budget, the debt-to-GDP ratio in Switzerland is below 30%.

UK vs Switzerland Debt-to-GDP

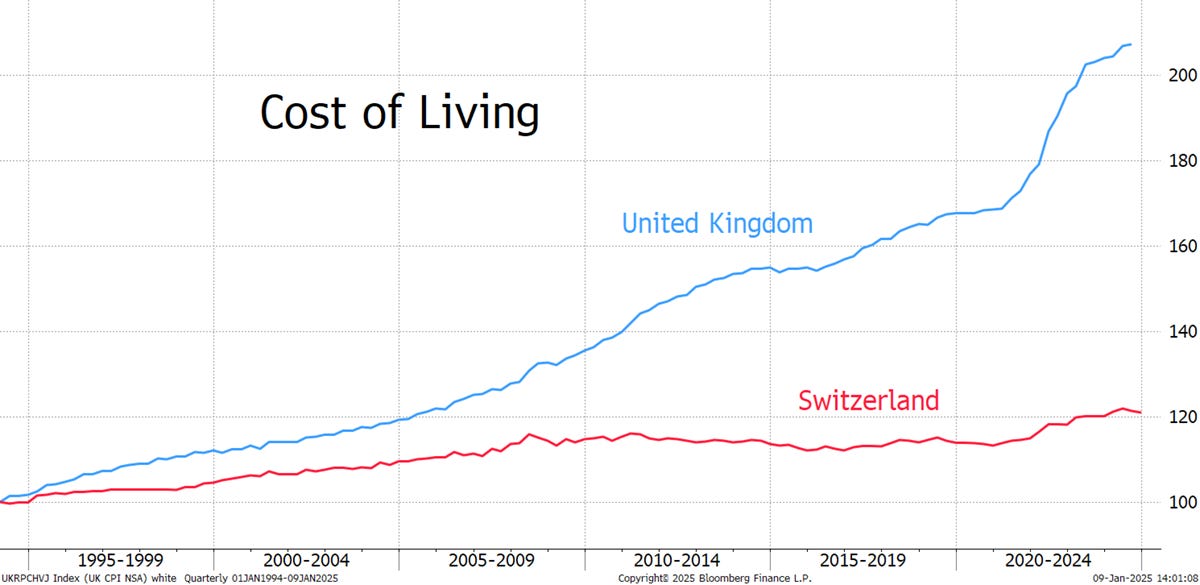

Many economists associate inflation with government deficits because they create money that goes into circulation. More money chasing the same number of goods and services sees prices rise. It is noticeable that UK inflation (using CPI, not RPI) has been consistently higher than Swiss inflation. Notice how UK inflation was briefly lower than Swiss inflation in the period when the UK had a budget surplus.

UK vs Switzerland Consumer Price Inflation

Economists think of inflation as the change in prices over the past year. Consumers see it differently because when prices rise, they never seem to fall back to where they came from. If you compound the yearly inflation so that all the years are combined, we get an idea of the cost of living. In the UK, it has more than doubled over 30 years, whereas in Switzerland, it has risen by 20%.

Cost of Living in the UK vs Switzerland

The difference between the cost of living impacts the exchange rate because it reflects the difference in purchasing power. Total Swiss inflation of 20% over 30 years means prices are 20% higher. In the UK, they are 110% higher, meaning the purchasing power of a pound has more than halved. It comes as no surprise that the fall in the GBP vs CHF exchange rate reflects the fall in relative purchasing power. It’s a remarkable match.

GBP vs CHF Purchasing Power and Exchange Rate

I hope this doesn’t sound political because it isn’t. A left-leaning government can tax and spend more, as we have seen in Northern Europe, where debt levels are low. A right-leaning government that favours lower taxes and spending can also succeed, as we see in Hong Kong and Singapore. What matters is that governments are competent, and regardless of their political persuasion, they should balance the books. If you don’t do that in business, you die, so why are governments any different?

The Swiss political system naturally leads to prudent fiscal outcomes whereby the government rarely spends more than it receives, and when it does, that is normally at a time of crisis. Once the crisis has passed, they are quick to balance the books and reduce public debt.

In the UK, recent governments have over-promised and have spent as much money as they could to win favour with the electorate. Both the right and the left have left this mess since the Major/Thatcher era when public finances were last kept in good order. Blair/Brown saw the UK debt double in the aftermath of the financial crisis. The Conservative/Lib Dem coalition took over in 2010, making little progress in reducing the debt at a time when the cost of borrowing was historically low. Then Johnson/Sunak took the reins in 2019 and spent heavily during the pandemic.

The UK grew debt-to-GDP by 20% during the pandemic. The Swiss grew it by 5% and have already paid it back. Today, the UK has a debt that is larger than the economy, and the cost of borrowing is no longer low like it was before the pandemic; it is high and rising. Last year, the debt interest bill was twice the defence budget, and this year will likely exceed education.

The solution is simple. All governments need to be more like the Swiss and less like the British. Balancing the books should be a statutory, and a moral, requirement. The alternative is to max out the nation’s credit, which, while fun for a while, is unsustainable. Countries that balance the books enjoy lower inflation, a stable cost of living, a firmer exchange rate and a lower cost of borrowing. Avoiding deficits keeps debt at bay, which leads to a more prosperous society for all.

This is important because some countries are highly indebted, such as Italy, the USA, the UK, France, Canada and Spain. Others are in great shape, such as Switzerland, Mexico, Indonesia, Australia, South Korea, and the Netherlands. As an investor, you are free to choose.

In my next piece, we will look at the risks and rewards of embracing these countries and the difference between investing in their bonds or their equities.

In the My Journey in Finance series, ByteTree Founder Charlie Morris shares lessons learned during his three-decade-long professional career in finance and investing.

We would love to hear your feedback, so please share your thoughts in the comments. It would really help us if you could like, restack/share this update and subscribe to our Substack. Thank you so much for your support!